Editors’ Note: Lindsey McDougle continues HistPhil’s forum on the Inclusive Study of Global Philanthropy, with a post on an experiential philanthropy class in Tanzania.

How do young people develop philanthropic identities—identities that empower them to make a meaningful contribution to their own communities? This is a question that I’ve often thought about; and it is ultimately a question that led me to dedicate the last several years to researching and practicing a unique approach to teaching philanthropy commonly referred to as “experiential philanthropy.”

Experiential Philanthropy

Experiential philanthropy is a transformative service-learning pedagogy that goes beyond traditional classroom instruction by allowing students to actively engage in philanthropic decision-making around issues and causes that matter to them. In doing so, experiential philanthropy is intended to nurture students’ philanthropic identities and strengthen their commitment to philanthropy.

This type of hands-on experience, studies have shown, can be crucial for philanthropic identity development. In my own classes, for instance, I have found that before participating in experiential philanthropy students rarely see themselves as philanthropists—even though a philanthropist is merely someone who is willing and capable of making a meaningful contribution to effecting positive change, in this case through the provision of material resources.

Indeed, philanthropy, which etymologically means ‘love of humankind,’ is a fundamental aspect of human nature. Throughout human history, cultures and religions have relied on philanthropy to create and maintain caring and harmonious societies. However, the contemporary image of philanthropy differs considerably from its etymological origins.

Today, philanthropy is often viewed as a lavish and overly conspicuous activity, and a philanthropist is often thought of as someone from a specific demographic—e.g., a wealthy individual who makes substantial financial donations or megagifts. As a result, for many young people, the idea of philanthropy, and by extension the idea of themselves as philanthropists, is unrelatable.

Experiential Philanthropy: Developing Future Philanthropists

This disconnect concerned me; and it should concern anyone interested in the future of philanthropy. Indeed, when young people struggle to see themselves as philanthropists, it raises critically important questions about the sustainability of the universal spirit of generosity that underpins our shared human values. Fortunately, experiential philanthropy offers a solution.

By participating in experiential philanthropy, studies show that young people begin to see themselves as more than merely beneficiaries of someone else’s generosity (whether monetary or otherwise). They begin to see themselves as active and capable agents of positive change in the world. In essence, experiential philanthropy empowers students to recognize and embrace their role and responsibility as philanthropists. It should come as no surprise, then, that an increasing number of experiential philanthropy initiatives have emerged over the past two decades (e.g., The Once Upon a Time Foundation’s Philanthropy Lab, the Mayerson Student Philanthropy Project at Northern Kentucky University, and the Doris Buffett-founded Learning by Giving Foundation).

Experiential Philanthropy: Developing Future Philanthropists Around the World?

Despite the growing number of experiential philanthropy initiatives and its empowering potential, the implementation of experiential philanthropy has primarily been limited to higher education institutions in the “Global North” (primarily in the United States and Europe). As a result, students in many other parts of the world have seldom had the chance to engage in the type of hands-on philanthropic learning that could profoundly reshape their understanding of and connection to philanthropy. It was because of this disparity that I set out to explore whether implementing experiential philanthropy in the east African country of Tanzania could be used as an approach to develop and nurture the philanthropic identities of young people there.

Philanthropy in Tanzania

The general concept of philanthropy has deep historical roots in Tanzanian society, stemming from the country’s strong communal values and traditions of assisting those in need. Historically, for instance, tribal communities have upheld the principles of “Ujamaa,” emphasizing collective responsibility and mutual support for one another.[1] Unsurprisingly, informal acts of giving reflective of this ideology tend to be prevalent throughout the country. Such acts often include assisting friends and family in times of need.

Formal philanthropy in Tanzania, however, is relatively rare. In fact, locally based formal philanthropy constitutes less than 20% of the revenue received by Tanzanian civil society organizations (CSOs). According to a 2018 report, the majority of funding for CSOs in Tanzania comes from international nongovernmental organizations operating outside the country; and, in the face of declining international development aid, Tanzanian government and charity officials have recognized the country’s need to bolster more locally based philanthropy.

Thus, while informal traditions of giving reflective of philanthropy’s etymological origins have long existed in Tanzania, the practice of formal philanthropy in the country is an idea that is only recently emerging. Consequently, few Tanzanians would likely consider themselves to be philanthropists—that is, as someone with the capability to make a meaningful contribution to effecting positive change in their community, through the provision of material or monetary resources.

Philanthropy, however, is a necessary and complementary force to the rich tradition of generosity and communal support in Tanzania. Indeed, philanthropy offers a more structured approach to addressing a wide array of social issues, e.g., economic inequality, gaps in public services, and disaster response. Strengthening philanthropy in Tanzania, thus, has the potential to foster innovation, encourage greater civic engagement, and promote sustainable development. Ultimately, by harnessing the power of philanthropy, Tanzania can build on its strong legacy of generosity and work toward a more prosperous and equitable future for all its citizens.

Experiential Philanthropy in Tanzania, at St. Margaret’s Academy

In an exploratory effort to assess whether experiential philanthropy could be used to develop the philanthropic identities of young people in Tanzania, I partnered with Margaret “Mama” Tesha, the founder of St. Margaret’s Academy, a private primary school in Arusha, Tanzania. Mama Tesha founded St. Margaret’s in 1993 as one of the first private schools in Tanzania. With just three students at the outset, she poured her heart and soul into the school, nurturing it into a thriving educational institution with an annual enrollment of nearly 500 students.

In the fall of 2022, with generous funding provided by the Do Good Institute at the University of Maryland and the Learning by Giving Foundation, I collaborated with Mama Tesha to organize a week-long experiential philanthropy module involving approximately 50 of the school’s sixth-grade students (the highest grade level at the school).

At the start of the module, I asked the students what they knew about philanthropy and whether they considered themselves to be philanthropists. As research on experiential philanthropy has shown, philanthropic identity is essential because it not only shapes students’ interest in future philanthropic activities, but it also influences their worldview and sense of purpose. Essentially, it empowers them to make meaningful contributions to society, fostering a culture of giving and social responsibility that benefits communities and the world at large. Not surprisingly, however, few of the students at St. Margaret’s said they knew much about philanthropy, and certainly none of them said that they considered themselves to be a philanthropist.

I then informed them that by the end of the week, they would have the opportunity to decide how and where $10,000 (US) would be awarded for the benefit of their community. They were shocked! In our discussion, they linked philanthropic efforts such as this to some of their favorite sports and entertainment figures. An opportunity like this was something Portuguese soccer star Cristiano Ronaldo or Tanzanian hip hop artist Diamond Platnumz did, they believed. As a result, they reported feeling proud. Proud that someone would trust them with such a decision.

Developing Philanthropic Identities at St. Margaret’s Academy

Each module for the week lasted four hours (including breaks and time for lunch). During the modules, the students participated in a variety of tasks and activities that focused on how they could use the money. Ultimately, they decided they wanted to give back to St. Margaret’s. There were things about their school community that needed to be improved (e.g., building repairs, cleaning supplies, school lunches, sports equipment, etc.). They wanted to contribute to its improvement.

The students decided to use the money to, first, improve the physical appearance of the school’s buildings. The buildings, they said (and I saw), had broken doors, cracked windows, and peeling paint.

One student noted, for instance, that “some of the door locks are broken and teachers put stones behind doors. So, we must donate some doors!” In agreement, another student followed up by exclaiming that “some windows are [also] broken and when it rains the rain usually enters through the windows. So, we must donate some windows!”

In general, the students felt that using the funds to improve the buildings at St. Margaret would instill within them a greater sense of pride in their school.

This decision marked a pivotal moment for the students.

All of the participating students could have personally benefited by choosing to donate to needs and issues facing themselves (e.g., using the donation toward the purchase of new school uniforms, family responsibilities, or even taking care of overdue school fees). However, they all chose to donate to something greater than themselves. They cherished the opportunity to give back to the school that they cared deeply about and that had nurtured them throughout their academic journeys.

This led them to begin considering other ways they could give back to St. Margaret’s:

We can donate a broom and a mopper! It will help us to remove dust and make our surroundings clean.

We can donate soap to help wash toilets and also help us remove disease!

We can also donate trees to plant in order to conserve our surroundings… and to give shadows and medicine.

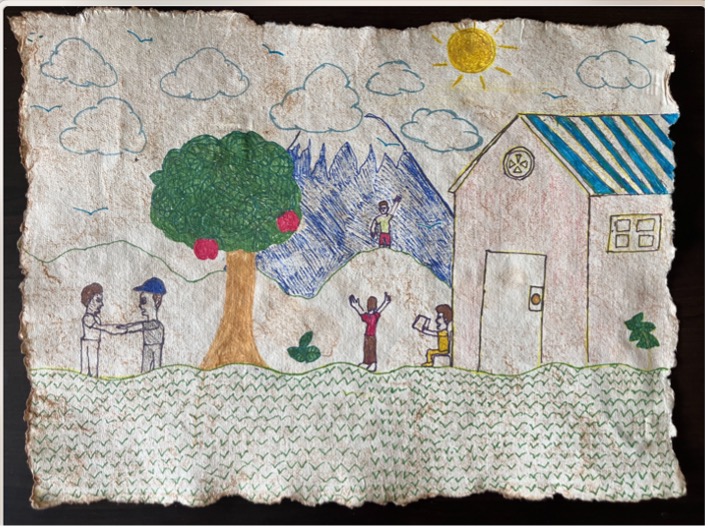

As the week drew to a close, a remarkable transformation had taken place. The students had not only developed a newfound appreciation for philanthropy—its true essence, i.e., love of humanity—but they had also embraced a sense of pride in being actively engaged in philanthropic endeavors for the benefit of their school community. Moreover, they realized that, even without money of their own, they already possessed valuable assets they could contribute in the future, e.g., their time, their voices, and their energy. In other words, bolstering their identities as philanthropists had encouraged their generosity more generally. Some of the ways that they saw their future selves engaging in philanthropy are pictured below:

The philanthropic efforts of the students at St. Margaret’s Academy have already begun to yield positive results. One noticeable change, for instance, is the rejuvenation of the school through a fresh coat of paint (shown in images below). School administrators have also actively begun working toward fulfilling the students’ other plans for the school, e.g., purchasing cleaning supplies, improving the quality of meals, and repairing broken doors and windows.

The impact of the students’ philanthropy has ignited a spirit of enthusiasm throughout the school; and, undoubtedly, as the school continues to embrace the students’ ideas and plans for improvement, the transformative power of experiential philanthropy will become even more evident. Indeed, the students’ philanthropy will continue to shape the future of St. Margaret’s Academy and will leave a lasting legacy of their kindness and compassion.

The Takeaway: Illuminating the Path Forward

Philanthropy is not just an act of giving; it is a way of fostering empathy, compassion, and a sense of responsibility toward others. This is a lesson that should resonate universally and should, thus, be taught in schools around the world.

Fortunately, experiential philanthropy offers a way to teach this lesson. Indeed, experiential philanthropy allows young people to see themselves in philanthropy, and as philanthropists.

Ultimately, as educators we hold the key to shaping future generations of thoughtful and compassionate individuals—philanthropists who strive to make a positive impact on the lives of others.

Mama Tesha took this privilege and responsibility seriously. I would be remiss, therefore, not to acknowledge that this project was only possible due to the encouragement and support that she provided. Mama Tesha had an immense love for children and instilled within all her students the belief that “education is my future.” Tragically, shortly after the completion of the module, Mama Tesha unexpectedly passed away.

Although she was unable to witness the tangible impact of the students’ generosity, she would be overjoyed to see what the students have done for St. Margaret’s. Mama Tesha’s unwavering advocacy for all children and her infectious passion for education left an indelible mark on the hearts of many. To Mama Tesha, education was not merely a pathway to knowledge but the key to a brighter future. Her belief in the transformative power of education continues to inspire not only the students she taught, but all who were fortunate enough to cross her path.

By involving the students at St. Margaret’s Academy in philanthropy, Mama Tesha helped inspire these students to become change-makers in their school community. And it will likely be these students who will carry the torch of philanthropy forward, lighting the path toward a brighter and more compassionate Tanzania for generations to come. Indeed, education—as Mama Tesha would say—is our collective future.

-Lindsey M. McDougle

Lindsey McDougle is an Associate professor and director of the Ph.D. program in the School of Public Affairs and Administration (SPAA) at Rutgers University–Newark. Dr. McDougle was a two-term board member of the Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action (ARNOVA) (2016–2019 and 2019–2022) and is a former editor-in-chief of Journal of Public and Nonprofit Affairs.

[1] See for instance Connie Ngondi-Houghton & Andrew Kingman, “The challenge of philanthropy in East Africa,” in Tade Akin Aina and Bhekinkosi Moyo, eds., Giving to Help, Helping to Give: The Context and Politics of African Philanthropy (TrustAfrica, 2014).