Editors’ Note: Nancy Um and Matthew Westerby introduce findings from the Scholars Data Project, hosted by the Association of Research Institutes in Art History, on residential fellowships sponsored by four leading research institutions in art history over the last six decades.

Each summer, humanities scholars in the United States (and beyond) eagerly await the opening calls from programs that grant research fellowships. Some of the most coveted grants are offered by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), as well as private organizations that make grants to individuals, such as the American Council for Learned Societies (ACLS). Others are offered by museums, libraries, archives, and research institutions, including the American Academy in Rome, the Newberry Library in Chicago, the Folger Institute in Washington DC and many more, which host scholars in residence, providing the opportunity to work with their collections, while engaging with their communities.

The dollar amounts of these individual grants, often intended to cover partial salary for a faculty member on leave, may seem minor compared to the hefty multi-year awards which have propelled forward research and innovation in the fields of science, health, and technology, bolstered by major federal agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation (NSF). Yet, these smaller grants provide critical support for the humanities and the humanistic social sciences by facilitating the advancement of individuals through the university credential and reward system. Such awards support pre-doctoral students to complete their dissertations and offer temporary teaching relief for professors, thereby positioning them for success in tenure and promotion. These programs also provide opportunities for collaboration, while supporting high quality work and encouraging important scholarship that may require an extended gestation period.

The sum of these awards has never been gauged in a holistic manner, even while most institutions publicize their scholar awardees on their websites and through press releases each year. Because of the dispersed nature of these individual grants, which each operate on their own timetables and terms, long-term funding patterns across institutions are thus difficult to assess. At this dire moment when so many sources of support for advanced research across domains, including many of the federal funding bodies mentioned above, have been disrupted by major funding cuts, new restrictions, and cancellations, it is crucial to take a broad-reaching look at the ways in which public and private entities have supported academic research, and particularly for the understudied realm of the humanities. In this light, this essay describes the findings of data collection based on four major residential scholarly programs in the history of art.

Scholars Data Project, hosted by the Association of Research Institutes in Art History

Beginning in 2024, four research institutions in art history elected to aggregate the awards data for their residential scholars programs. They are the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, National Gallery of Art (The Center) in Washington DC,[1] the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown MA, the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, CA, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in Washington DC. (Figure 1) Since the first of these programs was established in the 1960s, each has provided opportunities to scholars in the field of art history and related disciplines in the visual arts and humanities. All of the institutions are associated with collections of art, archives, and libraries. All programs support scholars across career stages, except for the Clark which focuses on established scholars. All are open by application and engage rigorous selection processes. All are also member organizations of the Association of Research Institutes in Art History (ARIAH), which has provided an online platform to present this data in an interactive story: https://www.ariah.info/news-opportunities/scholars-data.

Figure 1: Running Total of Scholars by Year and Program. This bar chart shows the sum of scholars funded across all four programs, 1961-2025, and provides a view of their scale and relative histories of funding. An interactive version of the chart can be found at https://www.ariah.info/news-opportunities/scholars-data (Slide 2).

The four institutions agreed upon a standard set of limited data points to include along with some program-specific categories. All also agreed to include only public data that had been previously published or announced. Each scholar was identified by either an institutional affiliation or their city of residence. This is point-in-time data, reflecting the status of the scholar as declared in the application or at the time of award. All data from the project is openly available in a raw format from a GitHub repository.[2]

Findings

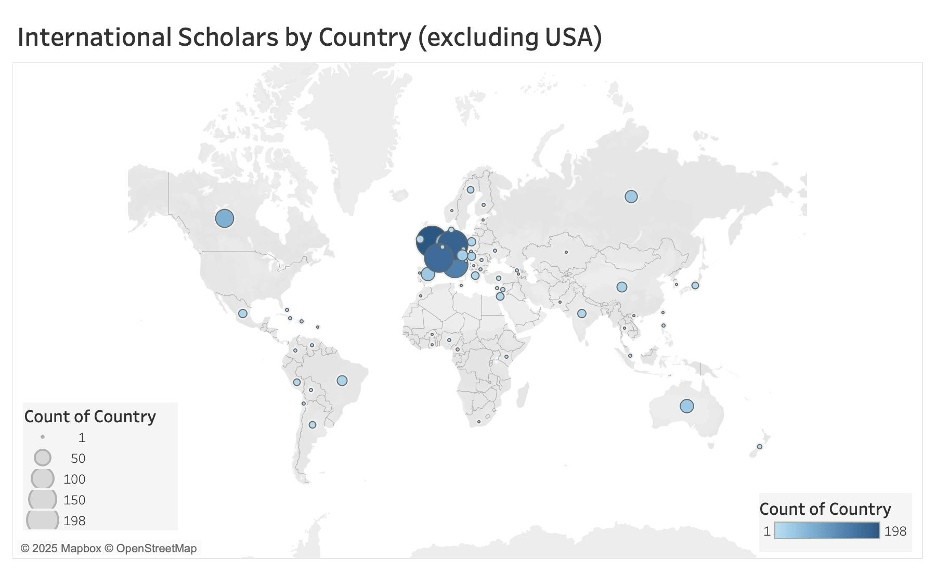

Between 1961 and 2025, the four programs funded 3,877 scholars. The majority of these scholars were affiliated with an institution; only 8% did not declare an affiliation and are recorded as an independent scholar. Each scholar was also associated with a geographical location, based on either the location of their institutional affiliation or the city of residence for independent scholars.[3] Since 1961, scholars who resided in or were affiliated with institutions in 72 countries have been funded by the four programs. While the majority of scholars (64%) have lived in the United States or been affiliated with US institutions, the map also represents a wide scope well beyond the domestic sphere. (Figure 2) However, awards have not been distributed evenly across continents or world regions. Outside of the US, western Europe and the UK are represented most amply, with 5% of all scholars from the UK or Germany and 4% from France or Italy. All other countries constitute 2% or less of the total funded scholar pool.

Figure 2: International Scholars by Country, excluding the United States. This map indicates the distribution of international scholars (excluding the United States). The markers are scaled by size and color saturation, representing the large number of scholars from the United Kingdom and Europe that have received funding from the four institutions since the 1960s. Interactive versions of this map, including an animated version, and additional geographical data can be found at https://www.ariah.info/news-opportunities/scholars-data (Slide 4, 5, 6).

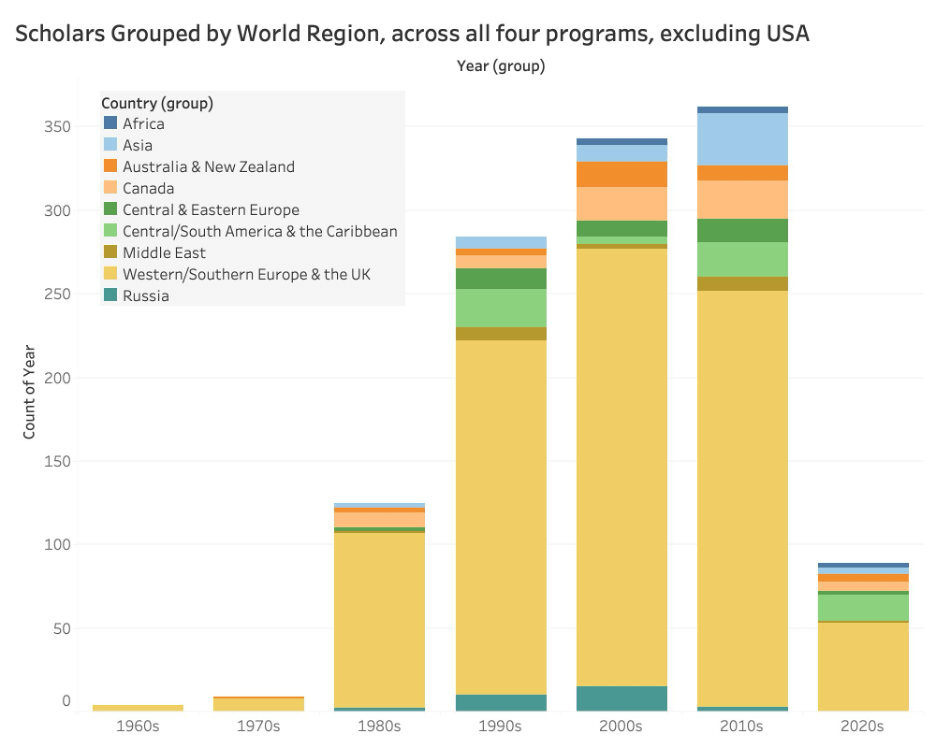

These numbers reflect the deep-rootedness of art history—as a discipline—in the Euro-American sphere even though that purview has shifted, incrementally, over the past half century, as indicated in figure 3. In the 1980s, scholars from Asia, Australia and New Zealand, Canada, Central and Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Russia first began to appear among the funded scholars. Then, starting in the 1990s, scholars from Central and South America constituted a prominent presence. In the case of Asia, we see a steady rise, beginning with 3 scholars in the 1980s and reaching 31 in the 2010s. However, Africa is minimally represented, with 4 or fewer scholars each decade since the year 2000 across all four programs. Russian scholars peaked in the 2000s.

This increasing international diversification can be attributed to intentional programmatic interventions. For instance, SAAM’s Terra Foundation Fellowships in American Art began in 2006 with the goal of promoting cross-cultural scholarship, made possible with external support. The Getty Foundation’s Connecting Art Histories program, which supports art history as a global discipline through collaborative international projects, began appointing fellows in residence at Getty in Los Angeles in 2010 and the Clark’s Caribbean Art and its Diasporas Fellowship began in 2021. Even while the range of countries represented among these scholar ranks has expanded over the decades, the orientation is still today weighted heavily toward the Northern Atlantic world. Reporting from the current decade is incomplete, but rising visa restrictions, as well as concerns about the reception of foreign scholars in the United States, is likely to result in a downward recalibration of this international scope.

Figure 3: Scholars Grouped by World Region, across all four programs, excluding the United States. This bar chart represents the changing dimensions of international scholars funded over the decades, with only partial reporting for the 2020s. An animated version of this geographical data, mapped and plotted over time can be found at https://www.ariah.info/news-opportunities/scholars-data (Slide 6).

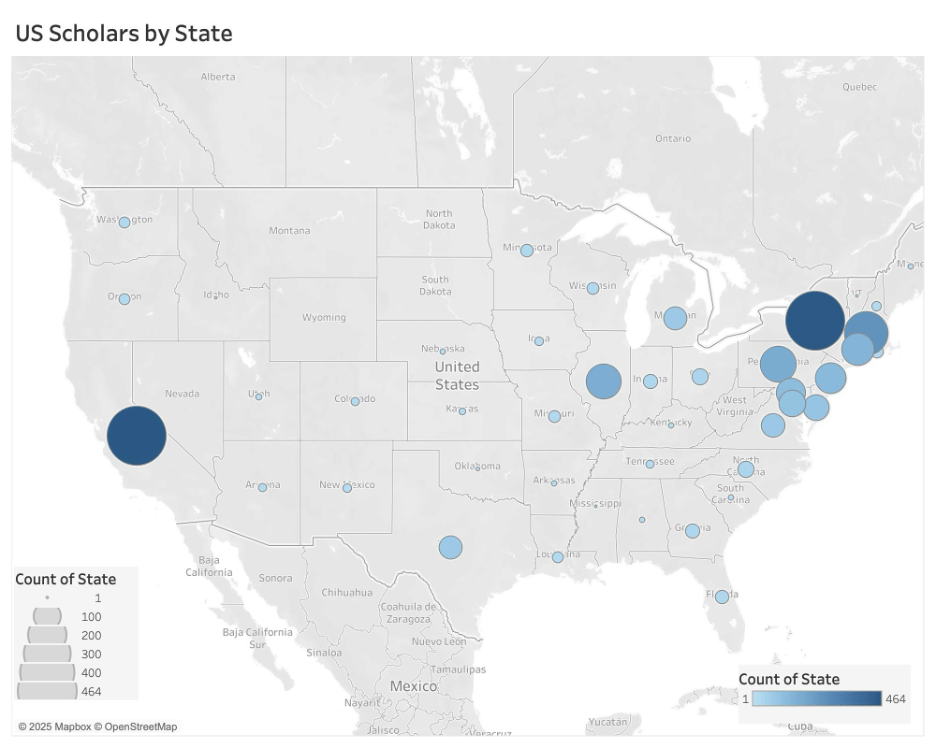

In the domestic sphere, the four programs have awarded scholars residing in or affiliated with institutions in 42 states and the District of Columbia. (Figure 4) The state that has received the highest percentage of awards is California at 18%, with New York trailing slightly at 17%, followed by Massachusetts at 9%, and Pennsylvania and Illinois, both at 6%. By contrast, there were 8 art history cold spots in the United States, where scholars have never been awarded from any of the four programs: Alaska, Hawaii, Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, South Dakota, West Virginia, and Wyoming. Similarly, Vermont, Idaho, and Mississippi were each represented by only 1 awarded scholar across this extended time period. There are no art history PhD granting institutions or ARIAH member institutions in any of those 11 states.

Figure 4: US Scholars by State. This map indicates the distribution of domestic scholarly affiliations or cities of residence by state. The markers are scaled by size and color saturation, representing the large number of scholars from California and New York that have received funding from the four institutions since the 1960s. Alaska and Hawaii are not pictured because there were no funded scholars from either state. Interactive versions of this map and additional geographical data can be found at https://www.ariah.info/news-opportunities/scholars-data (Slide 7, 8).

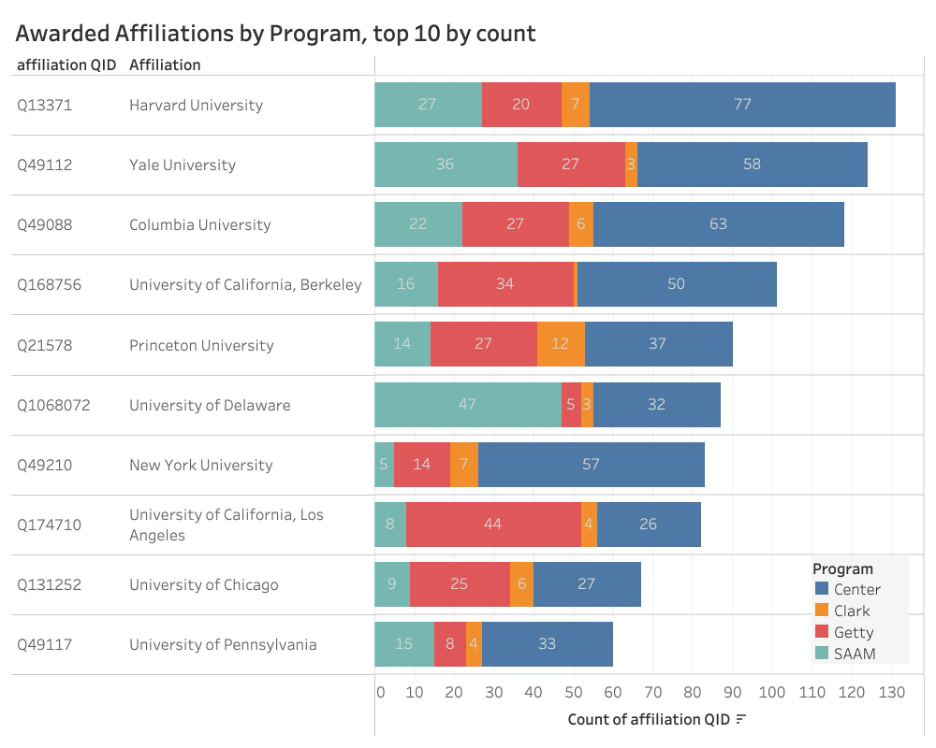

The majority of scholars are listed with an affiliation, which represents the place of employment for faculty and the degree granting institution for pre- and some post-doctoral scholars. The four programs have funded scholars affiliated with 784 distinct institutions around the world, including universities, museums, and research institutes. (Figure 5) The institutions that received the most awards during this time period were large research universities with doctoral programs, both private and public, namely Harvard, Yale, Columbia, UC Berkeley, Princeton, University of Delaware, NYU, UCLA, University of Chicago, and University of Pennsylvania.

Figure 5: Awarded Affiliations by Program, top 10 by count. This chart indicates the 10 institutions that have received the most awards since 1961. Interactive versions of this data can be found at https://www.ariah.info/news-opportunities/scholars-data (Slide 9, 10, 11, 12).

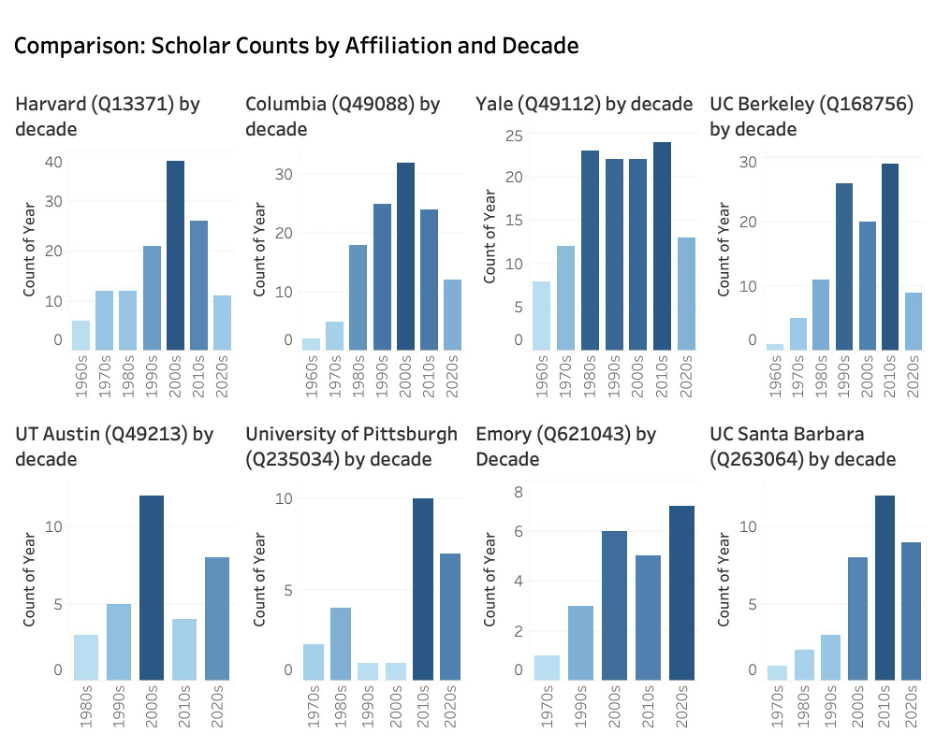

Additional nuance was added to these totals by exploring change over time. For instance, some of the large and long-standing programs reached funding peaks in earlier decades, while other smaller or younger programs show a rising trajectory of funding, even if their overall number of funded scholars may be much smaller. As an example, the patterns of funding for Emory, UC Santa Barbara, University of Pittsburgh, and UT Austin present an upswing in recent years, even while taking into account that the current decade is only reported partially. (Figure 6) Career stage is another significant dimension. The three programs that make awards to pre- and post-doctoral scholars (The Center, Getty, and SAAM) generally reported high numbers of awards to graduate students and post-docs, which outweighed those of the faculty, in some cases considerably. Of the Harvard awardee pool, for instance, around one fifth were senior scholars; the rest went to early career scholars, at the pre- or post-doctoral levels, who inevitably moved on to new affiliations after completing their degrees and appointments.

Figure 6: Comparison Slide of Institutional Funding by Decade. This chart compares the histories of funding for 8 institutions, highlighting the most awarded institutions (top row) and those that have lower overall numbers of scholars and shorter histories of funding, but with overall upward trajectories (bottom), based on only partial reporting for the 2020s. Interactive versions of this data can be found at https://www.ariah.info/news-opportunities/scholars-data (Slide 9, 10, 11, 12).

Conclusion

In order to pool this data, held by institutions in different formats, coordination was required. The Center and Getty produced a data template and generated persistent identifiers for institutions, which allowed for consistency and aggregation across programs.[4] These tools, now available for open use, provide easy ways for institutions to organize their data so that it can be connected with that of other institutions and be more durable for the future. Indeed, this project of data collection will continue, with the goal of garnering data from the four institutions for future years, while also bringing in other partner institutions.

External fellowship programs, such as the four included here, have provided crucial support for art historical research and advancement, as indicated by this view of funding patterns over six decades. Although it is by no means exhaustive, this study presents the direction that art history has been moving as the field has endeavored to expand its international scope and the range of degree granting institutions has grown across the country over time. It is also clear that funding bodies, such as the Terra Foundation and the Getty Foundation, and intentional programmatic initiatives have facilitated change in the field, spurring on increasingly broad internationalization, for instance. Moreover, faculty members in smaller programs have been successful in garnering awards in recent decades, among those from some of the more established and longer-standing research universities. It is yet to be seen which institutions will most successfully weather the rising challenges and threats that all academic programs are currently facing and how new needs and urgencies will shape the funding landscape of the future. But this information serves as a foundation for further inquiry in anticipation of this continuing evolution.

-Nancy Um and Matthew Westerby

Nancy Um is Associate Director for Research and Knowledge Creation at the Getty Research Institute, where she has purview over the Getty Scholars Program, research projects, academic outreach, and digital initiatives. Previously, she held the role of Associate Dean for Faculty Development and Inclusion in Harpur College at Binghamton University. Matthew Westerby is Digital Research Officer at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art, where he organizes scholarly initiatives in support of data-intensive research.

[1] National Gallery of Art funds used to sponsor its fellowships are solely from private sources.

[2] Westerby, M., Ferrara, L., & Um, N. (2025). Scholars Programs in Art History: Comparative Data Since 1961 (v1.0.0) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16612951.

[3] In some cases, this geographical location of a scholar’s affiliation diverged from the scholar’s nationality and/or place of residence.

[4] All tools, including a list of persistent identifiers (Wikidata QIDs for institutions), are available for reuse: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16612951.